Balantidium coli

| Balantidium coli | |

|---|---|

| |

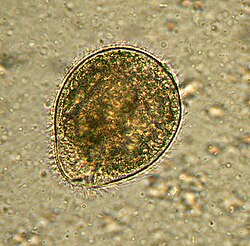

| Balantidium coli trophozoite Scale bar: 5 μm. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | Sar |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | Litostomatea |

| Order: | Vestibuliferida |

| Family: | Balantidiidae |

| Genus: | Balantidium |

| Species: | B. coli

|

| Binomial name | |

| Balantidium coli (Malmsten, 1857)

| |

Balantidium coli is a parasitic species of ciliate alveolates that causes the disease balantidiasis.[1][2] It is the only member of the ciliate phylum known to be pathogenic to humans,[1][2] although the main reservoir for this species are mainly domestic and wild pigs.[3] In addition, B coli is known to infect multiple species of mammal including cattle, camels, sheep, buffalo, and rodents, as well as some birds and marine mammals in rare cases.[3][4] B. coli has a world wide distribution, but tends to be spread more in humid and moist environments.[3] Infections in humans are commonly seen in tropical and subtropical countries in central and south America and Asia, although prevalence between each site can vary widely.[3][4]

Balantidium coli was first describes in the 1857 as Paramecium coli until being transferred to the genus Balantidium in 1863.[3] In 2013 after genetic analysis comparing B. coli with other species in the genus, isolating B. coli into its own genus of Neobalantidium was proposed, although it has been used interchangeably with the genus proposed in 1931 Balantioides.[3][5]

Morphology

[edit]

Balantidium coli has two developmental stages, a trophozoite stage and a cyst stage. In trophozoites, the two nuclei are visible. The macronucleus is long and sausage-shaped, and the spherical micronucleus is nested next to it, often hidden by the macronucleus. The opening, known as the peristome, at the pointed anterior end leads to the cytostome, or the mouth. Cysts are smaller than trophozoites and are round and have a tough, heavy cyst wall made of one or two layers. Usually only the macronucleus and sometimes cilia and contractile vacuoles are visible in the cyst, however, both nuclei are present because nuclear multiplication does not occur when the organism is a cyst.[6] Living trophozoites and cysts are yellowish or greenish in color.[7]

Transmission

[edit]Balantidium is the only ciliated protozoan known to infect humans. Balantidiasis is a zoonotic disease and is acquired by humans via the feco-oral route from the normal host, the domestic pig, where it is asymptomatic. Contaminated water is the most common mechanism of transmission.[8]

Role in disease

[edit]Balantidium coli lives in the cecum and colon of humans, pigs, rats, and other mammals. It is not readily transmissible from one species of host to another because it requires a period of time to adjust to the symbiotic flora of the new host. Once it has adapted to a host species, the protozoan can become a serious pathogen, especially in humans. Trophozoites multiply and encyst due to the dehydration of feces.[9]

Infection occurs when the cysts are ingested, usually through contaminated food or water. B. coli infection in immunocompetent individuals is not unheard of, but it rarely causes serious disease of the gastrointestinal tract. It can thrive in the gastrointestinal tract as long as there is a balance between the protozoan and the host without causing dysenteric symptoms. Infection most likely occurs in people with malnutrition due to the low stomach acidity or people with compromised immune systems.[8] In acute disease, explosive diarrhea may occur as often as every twenty minutes. Perforation of the colon may also occur in acute infections which can lead to life-threatening situations.[8]

Life cycle

[edit]

Infection occurs when a host ingests a cyst, which usually happens during the consumption of contaminated water or food.[1][9] Once the first cyst is ingested, it passes through the host's digestive system.[7] While the cyst receives some protection from degradation by the acidic environment of the stomach through the use of its outer wall, it is likely to be destroyed at a pH lower than 5, allowing it to survive easier in the stomachs of malnourished individuals who have less stomach acid.[7][9] Once the cyst reaches the small intestine, trophozoites are produced.[1][7] The trophozoites then colonize the large intestine, where they live in the lumen and feed on the intestinal flora.[1][7] Some trophozoites invade the wall of the colon using proteolytic enzymes and multiply, and some of them return to the lumen.[1][7][9] In the lumen, trophozoites may disintegrate or undergo encystation.[1][7] Encystation is triggered by dehydration of the intestinal contents and usually occurs in the distal large intestine, but may also occur outside of the host in feces.[1][7] Now in its mature cyst form, cysts are released into the environment where they can go on to infect a new host.[1][7]

Epidemiology

[edit]Balantidiasis in humans is common in the Philippines, but it can be found anywhere in the world, especially among those that are in close contact with swine. The disease is considered to be rare and occurs in less than 1% of the human population.[9] The disease poses a problem mostly in developing countries, where water sources may be contaminated with swine or human feces.[8] Use of contaminated manure as fertilizer and insufficient waste water treatment can lead to the contamination of crops and water supplies.[3]

The cyst life stage is considered infective due to its protective outer wall allowing it to survive the acidic conditions of the stomach, while the trophozoite is unable to tolerate acids of 5 pH or lower.[3][4] Cysts are able to survive up to 10 days outside of the host at room temperature, while in feces they can survive multiple weeks.[4] The trophozoite form however is only capable of surviving for a few hours outside of the host or up to a few days in feces or a moist environment.[4]

Diet can play a role in the susceptibility of the host to infection.[3] Captive and domestic animals being fed a high starch diets are commonly observed to have a higher prevalence of infection than what is observed in wild populations.[3] Captive and domestic animals can also have an increased likely hood of infection; B. coli is commonly reported in species of captive monkey and primate, where as their wild counterparts have lower prevalence.[3] Prevalence can also vary widely between species of host with the highest being observed in pigs, ranging anywhere between 30 and 100% infection in some populations.[3][4] In buffalo and camels a prevalence between 0 and 50% can be observed in India, Pakistan, and other middle eastern countries.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i DPDx Balantidiasis

- ^ a b Ramachandran, Ambili (23 May 2003). "Introduction". The Parasite: Balantidium coli The Disease: Balantidiasis. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Ponce-Gordo, Francisco; García-Rodríguez, Juan José (1 March 2021). "Balantioides coli". Research in Veterinary Science. 135: 424–431. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.10.028. ISSN 0034-5288. PMID 33183780.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ahmed, Arslan; Ijaz, Muhammad; Ayyub, Rana Muhammad; Ghaffar, Awais; Ghauri, Hammad Nayyar; Aziz, Muhammad Umair; Ali, Sadaqat; Altaf, Muhammad; Awais, Muhammad; Naveed, Muhammad; Nawab, Yasir; Javed, Muhammad Umar (1 March 2020). "Balantidium coli in domestic animals: An emerging protozoan pathogen of zoonotic significance". Acta Tropica. 203: 105298. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.105298. ISSN 0001-706X. PMID 31837314.

- ^ Pomajbíková, Kateřina; Oborník, Miroslav; Horák, Aleš; Petrželková, Klára J.; Grim, J. Norman; Levecke, Bruno; Todd, Angelique; Mulama, Martin; Kiyang, John; Modrý, David (28 March 2013). "Novel Insights into the Genetic Diversity of Balantidium and Balantidium-like Cyst-forming Ciliates". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (3): e2140. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002140. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3610628. PMID 23556024.

- ^ Ash, Lawrence; Orihel, Thomas (2007). Ash & Orihel's Atlas of Human Parasitology (5th ed.). American Society for Clinical Pathology Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ramachandran 2003, Morphology

- ^ a b c d Schister, Frederick L. and Lynn Ramirez-Avila (October 2008). "Current World Status of Balantidium coli". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 21 (4): 626–638. doi:10.1128/CMR.00021-08. PMC 2570149. PMID 18854484.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts, Larry S.; Janovy Jr., John (2009). Foundations of Parasitology (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 176–7. ISBN 978-0-07-302827-9.

External links

[edit]- "Balantidiasis". DPDx – Laboratory Identification of Parasitic Diseases of Public Health Concern. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013.

- "Balantidium coli". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 71585.